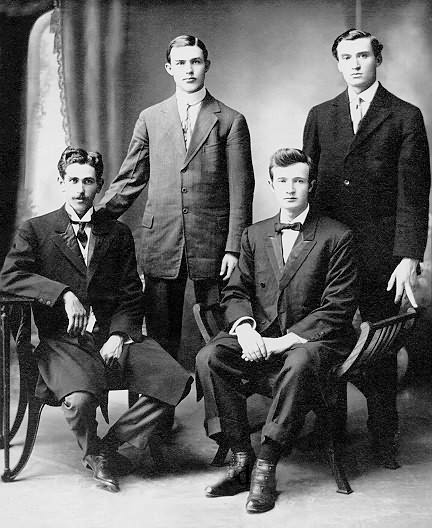

Lloyd Ivie during the Great Kanto Earthquake

(actual transcription,

page 5-6)

LDS

Missionaries, 1912. Ivie Choro Sitting far right.

(The Following

Information was Provided by Provided by, D. Staples, Kansai Branch,

Japan.)

When the Earth Begins to Tremble.

. . . continued

Our next move in that thirty-miles-in-a-day was to the Ginza and southward to Shimbashi Station,-- rather, the remains thereof; after which we headed in the general direction of Tsukiji. Who care if we went through the private garden of a wealthy merchant? There was nothing but the stumps of blackened shrubbery to greet us. Why shouldn't we cut across the grounds of an exclusive special school? No police-- or teacher-- or pupil came out to stop us. We detoured as much as a mile to find makeshift crossings over boat canals. In one place we watched a riverboat woman cooking a meal on open deck while a bloated and blackened corpse floated toward her. She pushed it away with her pole and returned to her cooking.

At last we stood@on the spot where mother had periodically gone during her pregnancy-- Saint Luke's Hospital, that frowned upon the long trip north. Only the fireplace of the reception room, amid warped and twisted iron that had been beds, remained. I was informed later that, during the interval between earthquake and fire, most of the patients had been carried out to safety, though not without hardships. Nevertheless "Thanks be to God" went up from my heart because mother was not there. If a lone and dreary feeling gives goose-pimples I had them. Perhaps the theme song of Burl Ives a decade later describes it, "I'm a poor,@wayfaring stranger, Travelling through this world of woe."

For two more hiking days we walked through the ruins. Along the banks of the Edo River we came upon an unfortunate creature lying on his back with nothing but a G-string for clothing. His two large toes were tied together with a thong, and his thumbs behind him in the same manner. He would emit invectives till his breath ran out; then spit in the air. A rod or two away stood a sentry. "What happened?" I inquired. "Pillaging", was the laconic reply. During martial rule execution before a firing squad is the penalty for that crime.

In Ueno Park every fence, statue, building, -- even the trees were plastered with notes upon notes of people inquiring after people, and instruction how to find them. There was a rice-line more than a mile long moving toward an army mess-pot at one end, while being added upon at the other. A ladel apiece was issued each day. When a nine-year old boy received his portion and sat down alone under a pine tree I approached him. "How long have you been here?" I asked. "I ran away from school after the quake". - Have you no relatives, friends, anyone you know?" - "There is no one". "Where do you go at night?" - "I sleep here, on the ground".

For years Yoshiwara was known to the traveling world. Few tourists missed it. Now it had become an escapeless incinerator. We saw roasted bodies strewn in tiny gardens where the heat had been so intense that it boiled the water and cooked goldfish in their ponds.

At Hifukusho 39,000 people perished. Burning buildings had trapped them. Then the vast area of surrounding conflagration consumed all the oxygen till everyone suffocated-- unconscious! -- after which the flames slithered in and finished the job. Less than two thousand were ever identified. A mere twenty-six came out alive. Kamiyama, a 19-year old student from Otaru was one of them. With bandages still on his arm and back he and I stood together on the spot where they had suffered; and where his sister had perished. As he toppled over in the blackout a gust of wind like a tornado carried her thirty feet away. The buckle on her school belt identified her charred remains.

Along the banks of the Sumida River bodies were fished out and piled like brushwood. Then they were saturated with kerosene, covered with pieces of metal roofing from the debris, and burned. We saw hundreds of such pyres.

On the following day, with our mission finished, we returned to Sapporo on a relief train. Millions of refugees were transported without charge to the provinces to be cared for. Even in small towns and villages groups were at the stations to give food and clothing. Children presented numerous relief bags made in homes and schools. As we commented on the compassionate unselfishness-- the astonishing efficiency we had seen in the herculean task of setting in order and caring for so many hurt and homeless victims,-- after we had sized upon the over-all magnitude of the disaster,-- we begin to realize that we, too, were on-the-ground witnesses to one of the greatest holocaustal tragedies known in all history.

Go To Page

4 (Epilog)

|